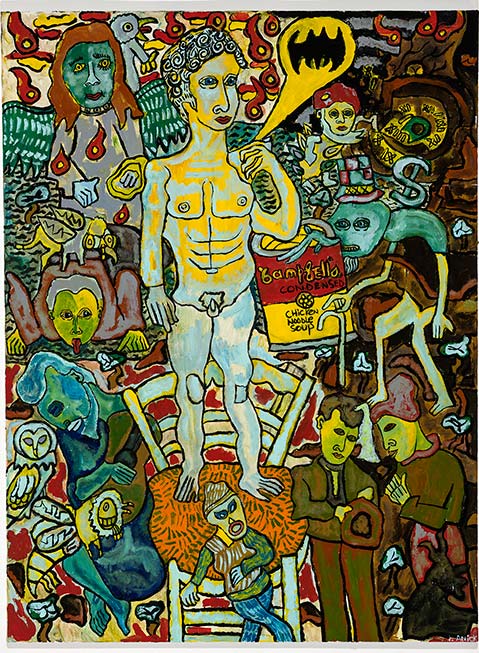

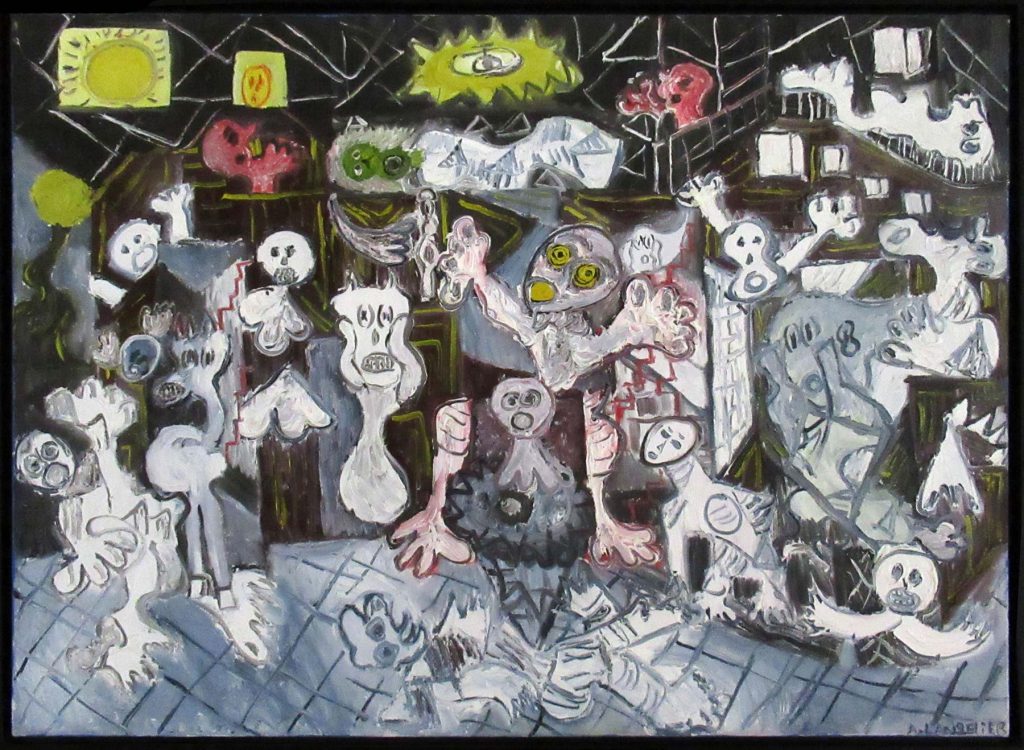

I read that Anick Langelier lived with the windows closed. The few paintings of hers that I have seen ─ very few out of the approximately four hundred she has created ─ appear to reflect this isolation through the proliferation of details and the intensity of expressions. This impression of lacking air may be exacerbated by the structure of many paintings in layered strips. We may think of the first comics drawn before speech bubbles were introduced, but also of interlocking squares that become more complex. But even more, this structure in irregular strips recalls the drawing of strata where, in archaeological digs, the successive cultures of humans who lived there appear. If the frame of the painting did not contain them by force, it seems to me that the strata in Anick Langelier’s narrative painting would stretch out and pile up along the length of the walls like frescoes. Was this structure not already present with the Egyptians, on Greek vases, in Aztec temples and in Romanesque bas-reliefs? Anick Langelier’s paintings are in that tradition, going beyond cultural specifities as she asserts her own memory of Christian and western art. Do not look for urban or rural landscapes in her work. The only frame is that of the painting in which the figures align or intermingle. Often heads occupy the space, known faces, like that of van Gogh, her favourite painter whose flames she made her own, merging with unknown faces, but all belong to the same gathering. Eyes staring, often hallucinated, sometimes turned toward our gaze without seeing us, they appear caught in the light of the painting, like deer in the headlights of a car driving straight at them. We think again of family photos taken by a violent father who orders his children to smile while looking at the camera. It is as if Anick Langelier’s figures don’t have the time to escape the dazzling speed of her paintbrush which freezes them. In the painting depicting the Last Supper, only Christ seems to escape this hypnotic threat, head tilted, supported by his hand, with a vacant look: a mixture of distress and boredom.

I’ve also read that Anick Langelier is a naïve painter. Perhaps for certain people, the presence of religious themes is seen as naïve art, perhaps the memory that guides the artist makes her the bearer of tribal art and that primitive art is too often confused with the childlike. I don’t see what is naïve in the way she reappropriates Egyptian frescoes or burns with Van Gogh’s flames. Anick Langelier’s painting is an elaborate, even if this work is in part unconscious. But perhaps the isolation necessary for her work as well as her survival led some to believe that, by making her a part of the cultural area, the protection of a ghetto of “raw art” had to be given to her along with the tag of “naïve painting” to double this isolation she continues to fight, not with naivete or madness, but with talent or genius.

Patrick Cady